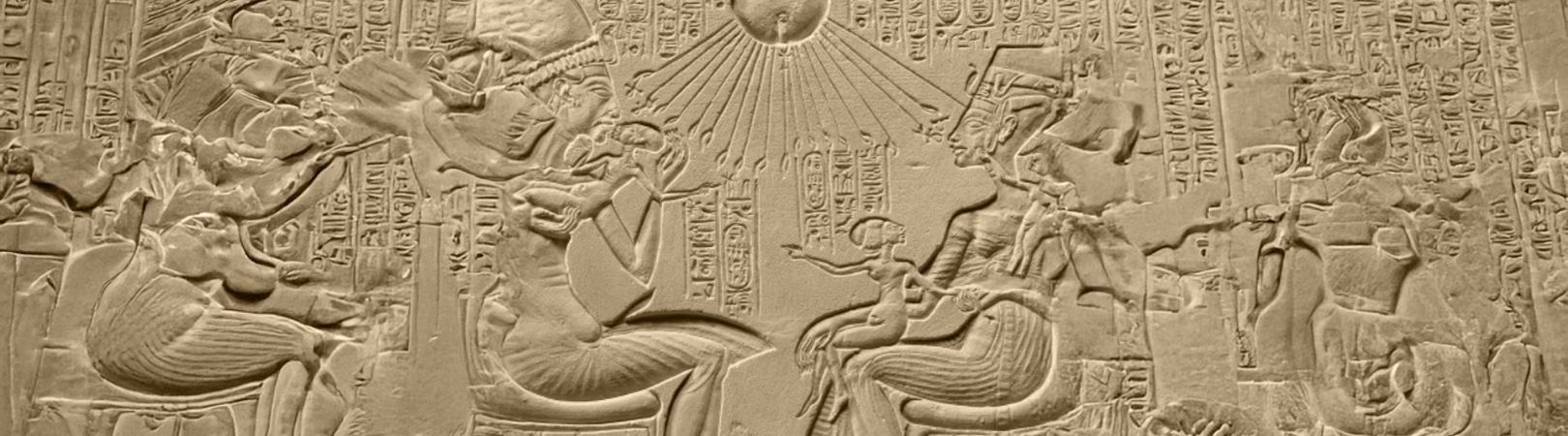

On the eve of his coronation as Pharaoh, eleven-year-old Amenhotep struggles with his father’s recent death and the responsibilities of his future reign. Haunted by memories of abuse and the expectations of the court, he battles inner turmoil as priests and priestesses perform rituals for the dead pharaoh. His mother, Mutemwiya, pressures him to choose a chief wife to secure her own position, but Amenhotep feels conflicted. Longing for freedom, he forms an unlikely bond with Tiye, a fowler’s daughter. Ultimately, the story subverts Amenhotep’s political arc, shifting its moral center to Tiye, who emerges as the true heroine.

Monument Man is deeply informed by the socio-political landscape of America (circa 2016–2020), particularly our collective trauma and trauma bonding to self-serving political leaders. The novella also draws from years of research into the Torah and ancient Egypt, originally undertaken for my doctoral dissertation. As the first installment of a larger reimagining of the Torah, Monument Man adheres closely to Egyptian source material while laying the groundwork for future protagonists like Moses and Akhenaten, whose connection Freud examined in Moses and Monotheism.

First 10 Pages:

1. Making of a Pharaoh

At first the boy could not be sure he had heard the voice. It was barely audible above the hissing embers on the brazier and quickly drowned out by the priests wrapping his father’s body inside the embalming tent out on the floodplain. With each layer, they slapped their armpits with cupped hands and chanted, “Ra, Ra, Ra, Ra, Ra.”

Below his chamber in the courtyard, Priestesses of Isis were determined not to be outdone by these priests from the House of Death. They shook their rattles and cried for Osiris to guide the pharaoh across the Great Nile in the Sky to the Field of Reeds.

“Go shut that,” his mother said.

Mutemwiya sat on a low stool lining her eyes with kohl in front of a plate of polished bronze.She wore a translucent white sheath and a beaded wig. He could tell by the ever-so-slight uplift at the edges of her tightened lips that she was relieved the old tyrant, Pharaoh Tuthmoses, was dead. She was also worried.

The boy went to close the window when the voice came with a fluttering birdwing of dark dread through his chest. He turned to his mother. “What did you say?”

She stopped applying the eye makeup. Her image wavered in the polished metal.

You are nothing, a nobody. Just like how his father used to say it. “There it is again.”

She spun on the stool, beads of her wig rattling. “Stop. Our time is running out.”

In three days, after his father was pulled by a hundred white bullocks wreathed with flowers up into the hills on a golden sledge, the boy would be crowned Pharaoh Amenhotep III. But that was only half the problem and not why she was sitting here now.

Again, the priests chanted and the priestesses’ moaned—all for show, no end to the courtly theatrics, as scripted by the gods. Not grieving for the dead pharaoh in this tenuous time as he was getting wrapped with linen and packed with amulets was to invite a malevolent spirit to shoot a wad of semen into the ear and take possession of the head.

This had happened to his father near the end of his life. He had been sitting on his throne when he went into a blank-faced trance. Though the priests brought him back with magical recitations, his lips hardly moved when he spoke. He couldn’t keep liquids in his mouth, he couldn’t chew on one side of his jaw, and he couldn’t get one eyelid to close.

He killed the priests who brought him back. He killed whoever looked at him blankly, unable to understand his strange, strangled speech. And when finding the boy in his mother’s dressing chamber wearing one of her sheathes, he took his staff to him in such a way that for days afterward, he couldn’t walk. Do you hear me? he slur-yelled.

Even over the shaking rattles in the courtyard today, yes, the boy could hear him.

He was nothing, a nobody.

His mother said, “The priests of Amen are sending another princess to your bed. I have examined her myself.”

As a minor wife of the pharaoh, Mutemwiya could claim her position as Mother to the Lord of the Two Lands only when the boy chose his chief wife. This had to happen in the next three days before coronation.

What if I choose you? he wanted to ask. “What if I choose nobody?” he said.

“It would leave Thebes vulnerable to spiritual attack. The priests would never allow it.” Beneath her beaded wig, the bridge of her nose was crooked from one of her own unlucky encounters with Tuthmoses’s ruling staff. “Please do this for me.”

****

The boy stood by the brazier sunk into the tiled floor, full of glowing embers, and pounded the base of his right palm against his head as he waited for the girl’s arrival.

Amenhotep, I am Amenhotep, I am the greatest—

The whole thing—this choice he had to make—was bringing on certain fears.

He had not been able to rouse his member since the priests of Amen had cut off the foreskin several months earlier, on his eleventh naming day.

The cutting away of skin, his mother said, had nothing to do with getting aroused.

He was not convinced. He had only the somewhat itchy wisp of brownish fuzz down there besides, not the full-on muff of hair he’d seen at the washing site on the day he met the man who brought the salted birds in earthenware jars to the pharaoh’s kitchen. The fowler had been singing a mournful tune in his Habiru tongue as he pounded his clothes on the rocks. Then he stood abruptly and turned to the boy, freezing him in place.

Amenhotep jumped at the soft knock on his door and told the girl to come in. He glanced at her. The girl wore a beaded wig, adorned with charms, and a tight sheath of a linen dress showing off her small breasts.

“Please,” he said. His voice cracked. “Wait for me by the bed.”

Sitting on a low cedar chest was a jug of wine and a platter full of grapes, figs, cheese, and roasted lotus seeds. The boy hadn’t remembered it being brought in, but from this point on, this is how it would go. Blink and whatever he wanted would appear, except the one thing he desired most: to see the fowler one more time.

After that first encounter at the washing site and others in the kitchen, they became friends and took walks together. On the day they found a dead hummingbird on the path, the boy was discussing his struggles with his father and his fears of one day inheriting the throne. The fowler squeezed his hand. Perhaps there is another way.

There was no other way. He was cursed to be Pharaoh. You are nothing. “Stop.”

The girl, who had been walking toward the bed, stutter-stepped.

“Not you,” he said. “Or yes, you. Take off your dress.” His voice cracked on dress. He cleared his throat and coughed into his fist. Then he really did cough—he had swallowed some saliva. He coughed and coughed and waved his hand wildly at her.

“Please,” he said between sputters. “Hurry up.”

He poured himself a cup of wine and sipped until the coughing subsided. He poured another and studied her more closely. She had henna vines wrapping her arms and breasts, meeting at a painted hummingbird digging its beak into a flower on her chest. How did she know about the hummingbird? Was this his mother’s doing?

His hands were shaking. They were like those of a girl’s, no larger or rougher than the girl’s hands holding onto the dress she didn’t seem to know what to do with.

Perhaps she had forgotten that part in her training.

“I would like to put on your dress,” he said. “Just leave it on the edge of the bed.”

She looked scared. “My lord?”

Her response consoled him. “I might like to put it on.”

She bit her bottom lip—in nervousness, or if she could cry—reminding him how very young she was. As young as him.

“I am only having a little fun with you,” he said, not realizing until he said it how true it was. He was only having a little fun. This wasn’t so bad. He could do this, his father the old tyrant getting wrapped out there in the dark or not.

She smiled and started to laugh. Though it started out fine, it soon built into something he’d never heard before, not from a human. Shrill in its jackal-like woofs.

He couldn’t imagine what his mother might have been thinking to send him a girl like this. It raked across the back of the boy’s neck, bringing with it the bone-tipped leather flail of rage to the tender edges of his flaccid heart. You are nothing, a nobody.

Quickly, he took the base of his right palm to the side of his head. “Shut up!”

The girl stopped laughing and looked at the floor.

“I wasn’t speaking to you.”

“My lord?”

“It is nothing. I am nothing.”

“But you are not nothing.”

He drank another cup of wine and swayed to the bed, scraping his foot against the floor. Then things became less clear. The smooth architecture of her body, milky in the moonlight, confused him. He couldn’t remember why she lay across his feather mattress with her back to him, waiting for him to mount her like any other common animal.

Above the hiss of the fire from the brazier, the Mistresses of Horus taking over for the Priestesses of Isis made it difficult to think. He imagined dark rivulets of blood from their self-inflicted wounds dripping down their arms. He couldn’t do the deed to their bellowing.

The girl was shaking. Was she chilled? No, afraid. He whispered into her ear from behind, “Tell me I’m nobody.”

“My lord?” A wobble at the edge of her voice, as if she might cry.

“Say ‘you are nobody.’”

She was sniffling. “I am nobody.”

“No. Tell me I am nobody. I am nothing.” His voice cracked on nothing.

“I do not understand.” She wiped her eyes. “You are soon to be crowned Pharaoh.”

“That is not what I said. ‘You are nobody.’ Say it.”

She said it much more slowly, her voice turning up at the end as if asking a question. “I am nobody?” She looked back at him.

“Not you. Me.” He raised his hand. She cried out and covered her head with her arms as if he might hit her. This brought a quick flash of heat to his cheeks. He’d only meant to take the silk pillow, traded for his pleasure from the East, out from under her head—probably ruined now with her runny lines of face paint.

The girl lowered her arms and whimpered.

He grunted as he crawled across the mattress, went for the wine, and drank directly from the jug. He burped, stoked the brazier, and steadied himself against the sooty column as he added a ball of myrrh to the fire to perfume the room.

He took up position behind the girl when he returned to the bed.

She would have been trained for this moment every day since the first appearance of her red moon. She had the pictures they provided her and the ointments the eunuchs in the House of Wives helped rub into her slit to make sure she was ready. He’d read all the reports. But why had nobody trained him?

The air was pungent with myrrh to the point of suffocation.

Perhaps he could talk with the girl. He wanted to learn her name and where she was from. Could she tell a good story? Could she play an instrument? Did she ever wish, like him, to lurch down the steps to the Horus fountain and throw herself in? Or walk into the western fields after Inundation and not return? Did she ever hear voices?

He ran his fingertips along her arm and down her hip and leg until bumps appeared on her skin and she moaned lightly, with pleasure. Then she wiggled her small buttocks and looked back at him. “My lord, is there anything I can do?”

“You could be quiet.” Immediately, he felt bad for saying it. “I’m sorry.”

“You don’t need to be sorry.”

“Well then, please do not look at me or talk. It makes me nervous.”

“As you wish,” she said, reaching back to grab his member. He recoiled.

Her somewhat steady palm, softened with oil, was as confusing as the fowler’s trembling, calloused fingertips on his cheeks had been comforting. It was the last time the boy wanted to be touched, moments before his father with a long string of saliva hanging from his lower lip stumbled into the room to find the boy wrapped like a nestling in the fowler’s arms.

But it wasn’t what his father suspected. The fowler and he had been looking for something to wrap up the dead hummingbird when the boy pulled out one of his mother’s sheathes from a basket and held it up to himselfin the mirror.

The fowler said, “Would you like to try it on?”

The question flooded the boy with happiness. He put it on behind a dressing screen and then came to dance for the fowler. The man laughed and clapped for him, and said, I can see it now, you will be different than him.

But the boy was too thin at eleven. He had a concave chest and a foot turning in from a birth defect. How could he become Lord of the Two Lands with his awkward gait? He stopped dancing. The people will laugh at me.

The man got on his knees to wipe the tears from his eyes, to caress his hair, and at last to bring him into his chest. The fowler was a Habiru, a despised class by the priests of Amen and therefore hated by his father. After beating the boy, Tuthmoses called for his guards to geld the fowler, spurting blood over his mother’s most precious garments.

The boy, made to watch, blinked the tears from his eyes but refused to turn away. He would not give his father the pleasure of knowing he had hurt him in any way.

The girl again turned back. “My lord?”

“I told you not to talk.” He smacked her on the head but not with any authority. Even so, she cried out and fell through the linen screen onto the floor. She lay there with a pillow over her head. He wanted to feel bad for her and he supposed he did.

“Leave me alone.”

The girl sniffled as she stood and tried to grab her linen sheath, but Amenhotep was holding onto it, gripped tight in his hand. She let it go. The patter of her feet was punctuated by her sobs as she ran naked from his chamber room down the hall.

****

He woke the next morning to the rattles of grief and a sharp stab of light coming through one of the high windows. He lay on pillows by the brazier in the girl’s dress. His mother was standing above him. She suggested a walk.

He dressed and met her in the courtyard. “I will choose nobody,” he said.

His head felt heavy as a block of stone from his first cups of wine the night before. He used his father’s staff to help steady him as he lurched along the path on his club foot. “Can I do that? Can I be both god and goddess to the Two Lands?”

“Surely there is one woman out of the hundreds in the House of Wives.”

“No. They’re all so—” But he didn’t know what he was going to say. Confusing? He looked out on the pleated hills at the edge of the floodplain on the western bank, cut with hidden tombs into which his father couldn’t be shoved quickly enough.

His mother said, “You think too hard on these things.”

His head was pounding now. He wanted only to return to his pillows and the dress. The thought of it encouraged him. The fowler, the last time they were together, had the tiniest quiver of a feather stuck to the perspiration on his cheek. The memory inflamed him. Also shamed him. He said, “I should really—”

He was about to say, get back, when a girl’s voice broke through to finish his words. Take up and read. It rose from the garden below. He went to look for her over the wall.

She was about his age, eleven or twelve. He was pleased to see her sidelock of youth bouncing against her thin frame as she chased the other children around the royal nursery. He recognized something in her gestures and the singsong tenor of her chant. It was from a game he remembered playing as a boy. I am still a boy. He wanted to remain a boy.

Take up and read, take up and read.

He broke off the bud of a red rose from the bush next to him and fingered its petals, trying to open them up.

“The girl,” his mother said.

“What?” He jumped.

“The girl, Tiye”—she motioned over the wall— “is the daughter of the fowler.”

He turned to her and whispered, “The fowler?”

His mother smiled at him beneath her crooked nose. She had planned it all along. The girl as his wife would remind the boy of his friend. He fumbled with the bud until he opened it up. He brought it to his nose. He said, “So let it be.”